Berlin Biennale 2018: not applause, but an alternative

In this blog, friend of Holy Biscuit Dominic White offers his view on this year’s Berlin Biennale. Dominic goes on to explore how he belives Christian artists could respond to making art, sharing it and building community in this often angry and broken world. He offers an interesting perspective on Christians in the arts which we would love to use to start a debate – feel free to comment below.

Berlin Biennale 2018: not applause, but an alternative

The artists are angry…

Really angry this time: “This sh*t is f*cked and we have to get out of this sh*t,” says the manifesto of this year’s Biennale (the 10th). In more philosophical language the About speaks of exploring “the political potential of the act of self-preservation, refusing to be seduced by unyielding knowledge systems and historical narratives that contribute to the creation of toxic subjectivities” (all quotations are from the website/guidebook, unless otherwise marked). But it’s a real cry against the toxic effects of the world’s growing and multiplying dictatorships, its “collective psychosis” and “incessant anxieties”, Trump, Putin and Erdoğan riding roughshod over democratic structures, the more subtle neglect and collusion of Western democracies in the abuse of migrants. The Berlin Biennale exposes all these, as well as forgotten, historical and often complex acts of oppression.

No to a saviour?

The anger goes further. This year’s Biennale is titled We don’t need another hero, from the song by Nina Simone who – back in 1985 – sang of wreckage and ruins, and not making the same mistake this time… The Biennale “rejects the desire for a savior”.

The kind of saviour who will sort out all our problems – if only we do as he says…? Jesus isn’t like that (of course!) And the doctrine of the Trinity, one God in three persons, reveals God’s statement for unity in diversity: so Christians can be at home with the artists’ desire for “different configurations of knowledge and power that enable contradictions and complications”…

But what does that mean to people, honestly? Even though mediation activities were party of the Biennale, the mood is still anger. Religious doctrine is already a matter of suspicion, and we know why…

This is a wake-up call for Christian artists. I’ll give an overview of the exhibition, which I visited with some of my Dominican brethren from Berlin. There’s plenty of good stuff, and some hope there. But the issues it raises demand much more of us than a round of applause. So I’ve also got some proposals for a serious rethink of what it means to be a Christian artist. Proposals for an alternative manifesto, if you like.

The art and the issues

One of the most pleasing things about this year’s Biennale, spread as usual across several venues, is the presence of many black women artists (previous biennales have felt rather white Eurocentric). Gabisile Nkosi and Grada Kilomba expose violence against black communities and, especially, black women. Emma Wolukau-Wanamba’s video Promised Lands reveals through a disconnect between spoken words and subtitles (“No being moved”, “Not here”…) (Figure 1) how Europeans have created utopias out of African lands – then colonised them and displaced the indigenous population. Wolukau-Wanamba herself has had some success as an activist for oppressed indigenous peoples. But beautiful videos of nature from a Puerto Rican barrio (poor quarter), by collective Las Nietas de Nonó, only highlight the violence of the neatly arranged surgical instruments and “women’s skins” made from vegetable leather arranged with them, recalling the “experiments” on black women’s bodies carried out by government, clinics and pharmaceuticals. Likewise Oscar Murillo’s sprawling work on bread would surely appeal to lovers of hospitality – though it’s a work that only serves to highlight the inhumane conditions of many workers.

Figure 1: ‘Promised Land’ by Emma Woluka-Wanamba

Dineo Bopape’s Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings] (Figure 2) is a massive installation, which also offers hospitality to other artists’ works. With an eerie red glow giving the impression of a bomb site, it’s inspired by Bessie Head’s novel A Question of Power (1973) about a woman’s descent into insanity, and includes a video of Nina Simone’s Feelings, itself evoking connections between madness and the colony. Nevertheless, as my Dominican brother Ulrich reminded me, there’s hope in the Biennale too. Lorena Gutiérrez Camejo’s multimedia ¿Dónde están los héroes? (“Where are the heroes?”) has four colourful groups apparently marching against each other over a crossroads (the cross shape accentuated by the aerial perspective), who then form a choreography together and mix up the “armies”. And Okwui Okpokwasili’s Sitting on a Man’s Head (Figure 3) offers a beautiful space for conversation and movement, though she is perhaps optimistic about people’s willingness to “tell another person’s story” to a stranger (I took the plunge with a Greek dramatist, but we were the only ones). North Europeans are generally too reserved for this kind of interactive art. Or is that the point?

Figure 2: ‘Untitled (Of Occult Instability)’ by Dineo Bopape Figure 3: ‘Sitting On A Man’s Head’ by Okuwi Okpokwasili

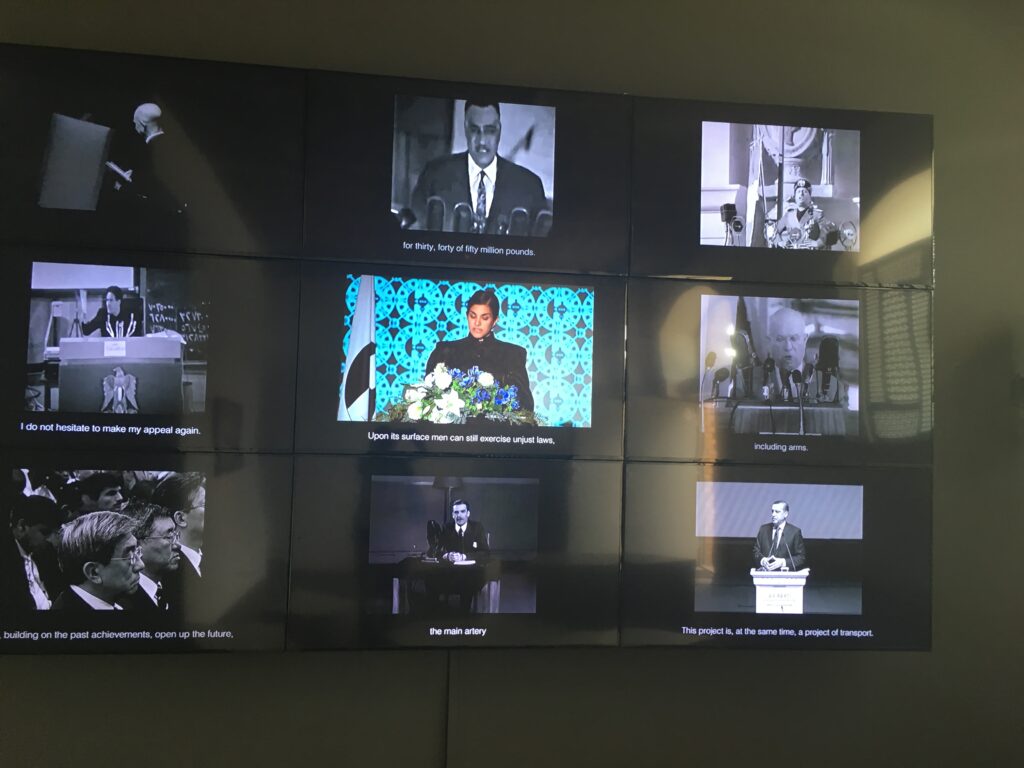

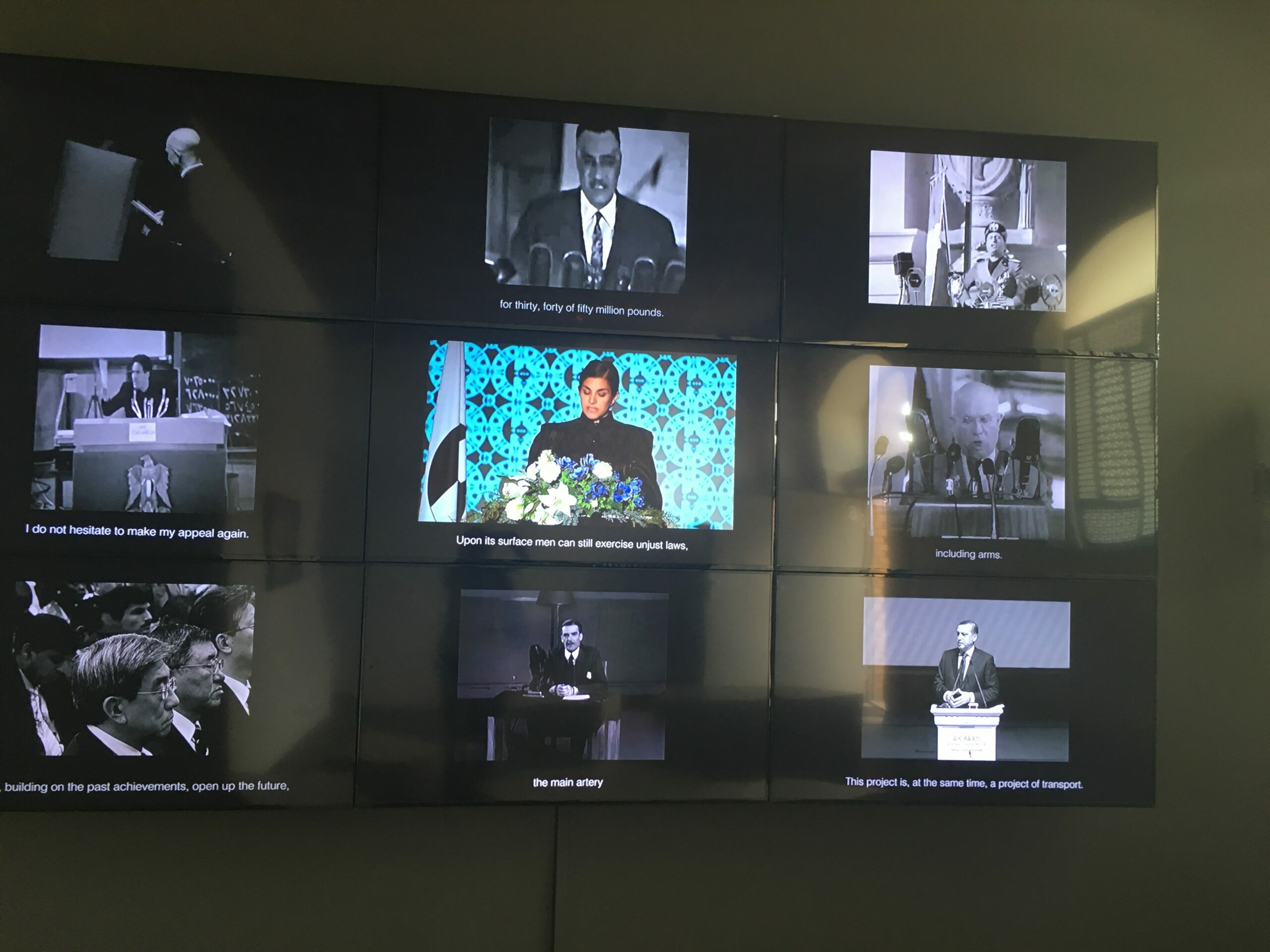

Some light relief came with Egyptian artist Heba Amin’s Operation Sunken Sea (Anti-Control Room) (Figure 4), which includes a screen on which are projected films of dictators and autocrats from Hitler and Sadat to Trump and Erdoğan. Sometimes the artist herself appears, and throughout, in a measured “UN” voice, you hear her describe, as leader of the new continent of Atlantropa, how “we” will drain the Mediterranean and pour it into the Sahara, and build a canal from Berlin to Cape Town to transport goods (cue Erdoğan’s new Bosphorus canal). Sunken cities will be rebuilt, and all the countries’ defence and anti-terrorism budgets will finance it. The Europeans need no longer fear mass immigration, and Africa will be fertile and wealthy. She seamlessly weaves in quotes from the autocrats: “”We will dominate the sea because we are grand” and “we” will just do it anyway, because “I’m sorry, but no one intervenes in our affairs.” It’s completed with a flag and her portrait. I laughed out loud. And then I shuddered, because I realised we’ve got used to this kind of rhetoric, and our acclimatisation only helps it become the new norm.

Figure 4: ‘Operation Sunken Sea (Anti-Control Room)’ by Heba Amin

Figure 4: ‘Operation Sunken Sea (Anti-Control Room)’ by Heba Amin

Mario Pfeifer’s video drama Again / Noch einmal exposes social breakdown in Europe. He gathers his own jury of German citizens to re-examine an incident in a small town in eastern Germany in 2016, when Shabaz, a mentally ill asylum seeker, threatened a supermarket cashier with a bottle. There were no police stationed in the area, and local vigilantes removed him and tied him to a tree, then contacting the police. Later Shabaz’s key worker resigned as he couldn’t cope, to be replaced by a far-rightist who neglected his medication. Shabaz disappeared – later his decomposed body was found in woods. There was a court case, the vigilantes (which they denied being) were prosecuted – and the judge dismissed the case. What emerges is institutional racism, the running-down of small communities (no local police), and most of all, for me, Pfeifer’s question, “How can we maintain a dialogue as society drifts apart?”

Surely this is the moment when the community-building Christians and the artists find themselves joining hands? Afraid not. Agnieszka Brzeżańska splices disturbing images from the news with esoteric symbols (she also casts spells, apparently), while “self-proclaimed atheist” Belkis Ayón got round the Cuban regime’s suspicion of religious art by making quasi-occult iconography about the Abakuá, a quasi-Masonic male secret society. I was struck by the beauty of Özlem Altın’s collage placed above the rooftop pond at the Academy of Art. Yet we’re told she “escapes the false bonds of religion. Her images don’t want to be holy icons, and don’t need to be.” Believers are all too familiar with the false bonds of religion that need purifying. But here there seems to be a deliberate rejection even of transcendence, that capacity of things to gesture beyond themselves to an invisible “more”.

Tony Cokes’ Black Celebration and Mikrohaus, or the black atlantic? expose a deeper difficulty for dialogue. Texts scroll on multiple TV screens against a background of pop music. For example, Mitt Romney saying of abortion provider Planned Parenthood, “We’re going to get rid of that” (he actually said, “We’re going to stop that”, but it’s still the kind of violent language an irresponsible man would use when his girlfriend tells him she’s pregnant). Next, it’s Pope Benedict criticising pre-marital cohabitation, and then Hillary Clinton tells us that extremists want to control women’s decisions about their actions and their bodies. This juxtaposition, in an exhibition which apparently wants to embrace contradictions and complications, seemed to me manifestly unfair. Many Christians, women and men, as well as Orthodox Jews and Muslims, oppose cohabitation because they believe it hinders lasting marriages. And a free, democratic society is founded on freedom of speech. My fear is that Tony Cokes represents a strong current in the arts community of being tolerant only towards people one likes: many difficult conversations, such as around sexual morality or abortion, are off limits. Of course, this mirrors the intolerance of fundamentalist politicians like Mitt Romney. But I thought the artists wanted to get us free of that?

An alternative manifesto?

As we’ve seen, the artists are angry, as we should be: about oppression, often hidden, but far more against a rising authoritarianism, with which religion, for historical and still current reasons, is often identified. But this means that as religious people, we already start the conversation on the back foot (and the Church abuse scandals are still emerging…). And perhaps the artists, for whom sensitivity is a creative need, are too hurt and angry to hear – perhaps they’re at that stage of grief where we hurt so much that we reject all offers of comfort?

So how should Christian artists respond? I’m going to say, let’s be more confident! Christians are often admired for our ability to build strong, sustainable community. The ground-breaking work of The Holy Biscuit on hospitality, in collaboration with non-Christian artists, has shown that Christian communities can really be a place where a diverse group of people can be welcomed/welcoming as both guest and host. Each one being fed and heard without judgement, embraced with the gaze of love, making friends, and “contradiction and complexity” (in the words of this year’s Biennale) being held from a strong centre. Because Christians believe that everyone, whether they believe in God or not – is uniquely made in God’s image – and we believe that in our lives God’s Word must incarnate in action.

So in this crisis of dialogue, let’s be confident that in a Christian context, the action of art has a unique power for the good. Here are my proposals towards a manifesto of our own.

-

To be a Christian artist is to show others what we have seen/heard in heaven.

The visionary of 2 Corinthians 12:4 was taken up to the third heaven (Paradise), where, literally translating, he/she heard “unspoken words that it is not possible for a human being to utter.” Some things cannot be said, which is why we need art, as it goes beyond ordinary words. For Christians, revelation, especially the Book of Revelation, is a vision into the heavens, a vision deeper into reality: a revelation of war, injustice and failure (including of the churches); but also a revelation of the triumph of the God’s love, a revelation of invisible but archetypal realities such as the Tabernacle and the Woman: deep, mystical realities (from the word “mystery”, as in, “Listen, I tell you a mystery”, 1 Corinthians 15:51). God’s revelation is of the real utopia of the New Heaven and New Earth. In “water and the Spirit” we ourselves were “born from above” (John 3:3, 5), that is, we were born from heaven. Our own inspirations, images and visions, even challenges (yes, ordinary things at which we wonder with a heavenly gaze), become art – if we accept the Spirit’s process of guiding and purifying us and our art, so that we can show heaven to others. This includes the vision of hidden evil (such as the revelation of abuse) – but always in the healing light and hope of the Resurrection. For a generation that doesn’t want a saviour, let’s show them what Jesus’ salvation looks, sounds and feels like.

-

Christian art is always incarnate – always heavenly, always humble

The Word become flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14). God became human, took a body, in order to reveal in Jesus the Father we could not see (cf John 14:9). He revealed heavenly reality, yet in the humility of a helpless baby and a crucified innocent, who emptied himself of equality to God, “taking the form of a slave” (Phil. 2:6-7). And he was incarnate in a place and time, embracing that culture, yet living and speaking free of its injustices. Recognising Christ in others, and open to and supporting and being challenged by everything which is good in our culture. And resisting all temptation to power over others, we speak the truth to power (sometimes in words), unafraid of rejection.

Some of us grew up in a Britain that called itself Christian (however hypocritically that cashed out). Now Britain is secular – 52% of the population say they have no religion. Trying to push back just makes us look arrogant, entitled, and in fact desperate. But: in reality, our society is pluralist – the other 48% are made up of people of different religions, including Christianity. One of the ways the established religious minorities, such as Jews and Muslims, have gained respect, affection and indeed interest is through hospitality and art. Jewish bagels and dreidels, pakoras on student Islamic society stalls, sweets at Eid; Jewish music and literature (and humour!), Islamic calligraphy and poetry from its Sufi tradition. We know we can do hospitality. Let’s do art, but that means we need to be…

-

…resourced from our tradition

In the past fifty years many Christians have distanced themselves from “traditional” Christian art, music, architecture and liturgy which had started to feel dry, irrelevant and (especially) associated with hegemonies of social control. Maybe the “Christian” state was already a form of secularisation… And we are not just guardians of “heritage”, theologising in the past tense. But in the face of strong Jewish and Muslim (and other) identities, who are we Christians? What is our art? We’ve seen an incredible rise of retro and vintage in recent years, led by twenty-somethings. A search for good things lost, that just need to be renewed? In the light of the interests of contemporary art, early Christian art such as that of a secret house church of persecuted Christians in third-century Syria, shows a rich cosmology of psychological depth, its stars and trees occupying and challenging the same territory as esoteric spiritualities (Figure 5). And quite simply, it’s beautiful. Alongside thriving contemporary Christian bands, centuries of classical Christian music has an abstraction and, again, psychological depth which resists all instrumentalising. Our cathedrals and communal houses (monasteries etc.) hold space, cosmic and human, which can speak to the challenges faced by contemporary urban life. Ancient forms of liturgy and song are rich in poetic word that gestures beyond platitudes to the inexpressible heavenly. The same liturgies are equally rich in gesture and movement: Christ’s choreographic body, the Church. But before we even try to connect our tradition with the contemporary, let us sit with it in silence, the silence in which God’s Word comes down (Wisdom 18:14-15).

Figue 5: A secret house church of painted by persecuted Christians in third-century Syria

-

Places of intellectual hospitality

Jacques Maritain, a prominent French intellectual and convert to Christianity, said that the true intellectual is anyone who wants to understand. In a time of massive pressure on academics to produce and sell knowledge, and a growing debating culture of attack and abuse, the hospitable and resourced communities of Christians can be places where people can ask and discuss their big questions, unafraid of being shot down. This was one of the works of monasteries during the Dark Ages (4th to 11th centuries), and of Jacques and Raïssa Maritain in their own home in the 1920s and 30s, times of social and political collapse. These communities became places of real learning for everyone – places of Wisdom.

-

Prayerfully work for the common good

Not just fighting the Christian corner, being nice busybodies, or finding ways to “get people in”, but being Christ’s brother and sisters for the poor, collaborating with all people of good will – the Dwellbeing project is a great example. But don’t expect the world to support, understand, or even like us. “Get out there” as much as we can, but also be open to self-publishing, as far as possible as communities rather than individuals. Not just being with the poor and marginalised, but being the poor and marginalised. At the same time, let’s be assured that rooted in prayer, working for the common good, showing what we have seen in heaven, we are already evangelising, already bearing the good news. The Spirit will tell us the moment to go beyond these lived parables and speak of Christ.

… “be thankful”: literally “become Eucharistic” (Col. 3:15).

And from this, a word may spring…

Fr. Dominic White is a Dominican friar and Catholic priest. Until recently a university and arts chaplain in Newcastle, he works as a Research Associate at the Margaret Beaufort Institute of Theology in Cambridge, where he is researching the theology of the gaze, and contributing to teaching Christian spirituality, as well as New Testament and theology of the Church for religious education teachers . He is the author of The Lost Knowledge of Christ: Contemporary Spiritualities, Christian Cosmology and the Arts (Liturgical Press, 2015), and is an organist and composer.