How Do I Look? Bodies and the Theotic Gaze

How do I look? We’re very concerned about how we look to others. Not least because we don’t know whether how they look – at us – will be kind. Every culture, every age, of course, has had its “standards” of beauty, many or all of which have caused suffering, especially to women. We might think of Victorian corsets, for example, which made women’s waists artificially small, and also restricting their ability to eat and even breathe. In our own age, the “standard” of beauty has taken artificiality a step further. The images of beautiful people you see on the front of magazines are not real, even if they’re top celebrities. They’ve been “corrected” using Photoshop, “blemishes” removed and proportions “perfected”. No wonder that so many people, not just adolescents, are caught up in “body talk” and plagued by it. The gym (especially the changing room), the swimming pool and the beach may be no longer places of recreation and freedom, but nightmares.

Behind this is something more fundamental: the gaze. This word, very important in psychoanalysis, Continental philosophy and film criticism, translates the French regard, and in fact contains the English sense of “regard” too. How I regard someone is both how I look at them and what I think of them. In other words, the gaze is a look of judgement. The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan argued that when we realise we are being looked at, we lose a degree of autonomy. We are less free than we were before. The philosopher Michel Foucault took this further: when we believe we’re constantly being watched (even if we’re not really), we regulate our behaviour accordingly. Now of course in Britain we don’t (thank God) live in a police state. But leaving aside profiling by internet search engines and social media, we do feel watched by people around us. Our neighbours, our colleagues, anyone who sees us in the street. Even our friends. Does he/she think I’m fat? Am I too flabby to appear in the gym? Too skinny?

The more basic problem with the gaze is to be found, according to the feminist film critic Laura Mulvey, in the male gaze which has dominated film especially (the man behind the camera). It has also formulated the canons of the “high” culture of Western art in general. We might consider ourselves mature and broad-minded in being able to distinguish between lad mags and classical female nudes, but the latter are not so innocent. It does not take long to realise that many are products of an eroticised male gaze, as controlling as Photoshop. Further, this gaze is often also colonial: as Fikret Yegül says, the popular, fanciful paintings of female nudes in Turkish baths by the celebrity Victorian painter Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema reflect “a privileged, Western male view of the beautiful naked world of Turkish women”. ¹ In other words, pornography for the educated Western male.

Faced with this frankly toxic situation in our supposedly liberal society, I was very inspired by three exhibitions at The Holy Biscuit this year, which offered new and liberating gazes. WE ARE WOMEN, a collaboration between The Holy Biscuit and Student Life at Northumbria, presented photos of women against a dark background. The power of photography is that it freezes time in a hectic world, giving us back time to contemplate what we see. The lighting was remarkable – I can only describe it as sympathetic, inviting us to see that beauty comes from within. And in the light of faith, we saw people made in the image and likeness of God. Especially striking was the interaction of word and flesh: the women had written on each other’s or their own bodies. “JOURNEY TOGETHER” on the soles of one woman’s feet; “Yesterday’s mistakes don’t define tomorrow’s path” on a woman’s back. Perhaps the most moving photo was of the arm of a woman struggling with self-harm, on which was written, “By his stripes we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5).

Hiatus was an exhibition by four female artists navigating life after art school – including the realities of the art world and life in general. Creating art between multiple jobs, with all the questions of work, finance and gender this raises, the artists respond in different ways. For example, Maria Abbott, in her installation and performance Wild Thing, reflects on the misogynistic male gaze of advertising and media. As Holy Biscuit Director of Programme and Development Alison Merritt-Smith writes in her essay Hiatus and G*D talk,

In Abbott’s work we see an expression of the frustration of the never-ending cycle of the commodification of women’s bodies and misogynistic control of women’s expression of their sexuality and individuality.

Alison also demonstrates that the Christian Church is not so innocent either. Christian (male) leaders have been complicit in misogynistic interpretation of Biblical texts, and have tended to focus exclusively on Jesus the Logos as male, while leaving out the feminine Sophia (Wisdom) aspect of God (cf Proverbs 8).

Maria Abbott, ‘Wild Thing’ 2016, 10-minute-performance at Hiatus, 7 December 2016

So Juliet Fleming’s Shrine to Femininity challenges our gaze, proudly celebrating the clitoris, as well as examining its representation in art and society. In the light of Christian faith this work reveals the goodness of a creator God who does not instrumentalise women’s sexuality as purely a means of production.

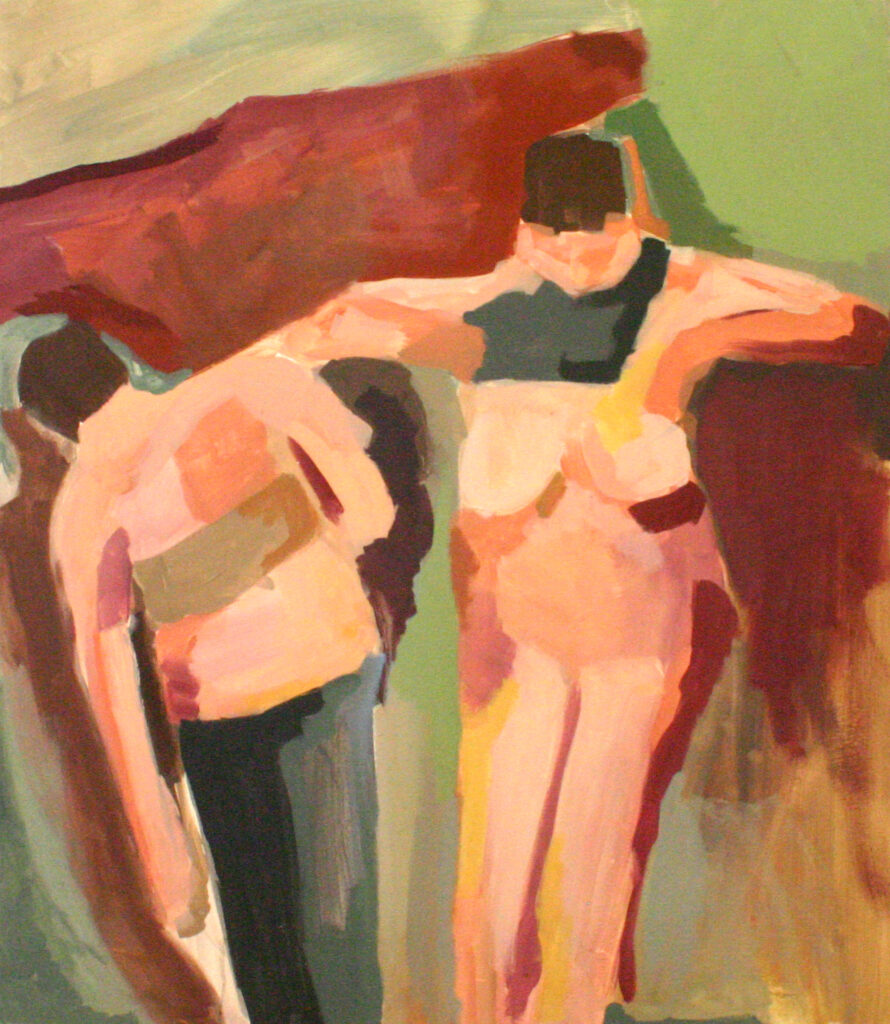

The third exhibition was Ladies Who Lunch Paint by four women, all of them at the time Newcastle University BA Fine Art students. I was particularly struck by the work of Molly Bythell, her paintings of female nudes had a softness of focus, a lightness and an understatement which, in a way I find hard to analyse, simply make you look differently. Not the conceal/reveal game of eroticism, but a school of seeing, discovering, wanting to see the person.

Molly Bythell, Nude painting

During the months these exhibitions took place I was reading the contemporary Catholic thinker Fabrice Hadjadj. Of Tunisian Jewish/Muslim parentage, Hadjadj was for many years an atheist. His views on the graced possibilities of the gaze are revolutionary:

The Lord is there and does not say, ‘Look at me,’ but, ‘Look at the lilies of the field’ […] The Word of God does not trample on creation, but rather, under his gaze of love, it appears in a dignity which is greater than royalty.² (cf Matthew 6:28; Luke 12:27)

In other words, the light of Jesus’ divine gaze reveals all creation – which includes every person – in all its true dignity.

Drawing on Hadjadj and on 2 Peter, I’d like to propose the idea of a “theotic gaze”. (Yes, I did invent “theotic”: I couldn’t find another word that would fit!). In 2 Peter 1:4 we read that God offers us the promise of becoming “participants in the divine nature”. The monastic tradition of Orthodox Christianity has meditated long on this phrase, and has come to understand that in sanctification (making holy), God makes us more human by actually making us divine. They call this theosis, “divinisation”. As we become sanctified/divinized by the Holy Spirit, we are increasingly Godly, doing what Jesus would do. And this includes how we look at others, at their embodied selves. As Jesus could look at the lilies of the field in a way that revealed them in all their glory, so we can gaze at others “theotically”. Like the photographer’s light in the WE ARE WOMEN exhibition, we can gaze at others in a way that reveals the person in all their real beauty, and thereby transforms them into the person they truly are.

The theotic gaze does not exclude the erotic, and may indeed include it. When Jesus condemned the gaze of lust (Matthew 5:28) he was not condemning sexual attraction, but rather the gaze which commodifies the other person as a means of sexual satisfaction. As preacher Timothy Radcliffe said in a student talk at Newcastle University, “The first step in loving another person is rejoicing that they exist.”

Of course, the theotic gaze, the look of divine love, is perhaps the most unrequited love. Indeed, the Jesus who gazed with divine love on the lilies of the field was rejected, put to a cruel death – and many of his followers after him, to this day. Perhaps this is because to be loved unconditionally for who you are, to be really seen, even to be just invited to be yourself, is absolutely terrifying, at least to begin with. The theotic gaze strips us of all artifice and pretence, all internalisation of societal expectation, all hiding. We are naked.

In this crisis we all must face, art might help us through. In the light of Christian faith, the works I have described, especially WE ARE WOMEN and Molly Bythell’s nudes, show us what being gazed at theotically actually looks like. We see how others are when they are seen, truly seen, and see their beauty. Maybe secretly, like the seed which has fallen into the ground and has died, slowly the desire will be formed in us to be seen and transformed by the Divine Light, and in turn, to see others.

- Fikret Yegül, Bathing in the Roman World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 226.

- Fabrice Hadjadj, Comment parler de Dieu aujourd’hui? Anti-manuel d’évangélisation [“How to speak about God today? An anti-manual of evangelisation”] (Paris: Salvator, 2012), p. 61 (my translation).

Fr Dominic White OP is Arts Officer at St Dominic’s Priory, Newcastle, and a chaplain to Newcastle and Northumbria Universities. He is the author of The Lost Knowledge of Christ: Contemporary Spiritualities, Christian Cosmology and the Art (Liturgical Press, 2015) https://lostknowledgeofchrist.wordpress.com/